Translation is the final step in the process that brings the very mind and words of God into our own hands in a language we can read. However, this task is challenging and fraught with difficulties. The way translators address these challenges leads to divergent results. Hence, there are numerous English translations, each of which differ to some degree. This section will address the reasons for the differences between English translations, and by doing so, hopefully providing some guidance in choosing a translation most suited for the sort of Bible study which we will detail later in the book. Differences between translations arise from (1) different translation philosophies, (2) different textual bases, (3) developments within the English language, (4) target reading levels, and (5) exegetical reasons.[1] After discussing these differences, we will address the question, “Which translation should I use?”.

Translation Philosophy

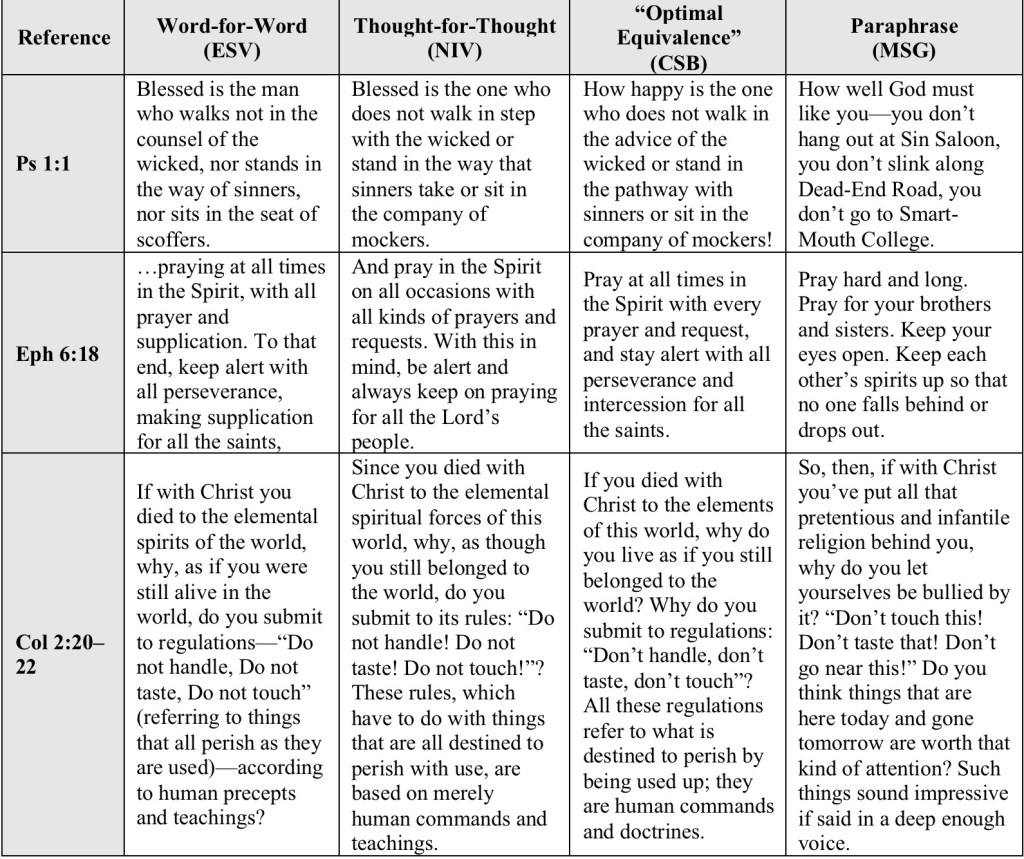

Translations generally fall along a spectrum between two approaches: word-for-word (formal equivalence) and thought-for-thought (dynamic or functional equivalence). In general, word-for-word translations, seek to represent the original language as closely as possible in the translation. The more word-for-word a translation is, the more literal—and perhaps wooden—it is. There are benefits to translations on this side of the spectrum: (1) there is less interpretation involved in the translation process, thus allowing the student of Scripture to make independent exegetical decisions; (2) its consistency in translating various terms, aids the student to pick up on repeated terms, phrases, and themes more easily; and (3) its consistency in reflecting the grammar and syntax of the original allows the student to better follow its structural flow of thought. However, there also some drawbacks: (1) its literalness can sometimes affect its readability and (2) at times, certain idioms and figures of speech can be lost on the modern English reader. Translations which generally follow this philosophy of translation include the NASB, ESV, LSB, KJV, and NKJV.

On the other side of the spectrum are thought-for thought translations. In general, these translations seek to reproduce in contemporary English modes of speaking the impact that the original text had on its hearers. To do so, instead of a wooden word-for-word translation, these seek to interpret the original idea that the Greek or Hebrew conveys and then render the same idea in a way that is natural to English readers. The main benefits to these translations include their readability in English and their ability to bring in people who are not familiar with “Christianese” language. The drawbacks though include losing all of the benefits associated with the word-for-word translations mentioned above. Translations which generally follow this philosophy of translation include the NIV, NLT and the CEV. Other translations land somewhere in the middle, such as the CSB, which attempts to achieve “optimal equivalence” instead of an either-or approach of formal vs. dynamic equivalence.

A third category that can be considered under the heading of translations is paraphrases. Although these are not technically translations from the original languages, they are important to discuss here since they are published as Bibles and are used in many worship settings. Paraphrases are even more dynamic than thought-for-thought translations. These are not tied to the original languages to any significant degree. They provide interpretations or commentaries on the text. The most popular of this category is The Message (MSG) by Eugene Peterson. To illustrate the differences between these translation philosophies, consider the following comparisons.

Textual Basis

Sometimes translations differ from each other not because of their translation philosophies but because they translate from different textual bases. As we saw in the previous section, textual criticism is the process by which someone seeks to establish the original text of Scripture by comparing the manuscript evidence and coming to a reasoned conclusion. Most modern translations use the most recent critical texts as their foundation. However, even while using these, in a few places, translators come to different conclusions on particular textual variants. This results in a different translation because they are translating a different text. These types of differences are fairly rare in modern translations since the vast majority of the text of Scripture is established beyond in reasonable doubt.

The more significant differences occur with translations that do not use the most recent critical editions in their translations, such as the KJV and NKJV. For the NT, these rely on a Greek text, commonly called the Textus Receptus (“received text”),[2] which is based on the Greek New Testament that Erasmus produced in ad 1516. This was a remarkable achievement which allowed scholars to go back to the original language of the NT instead of relying solely on the Latin Vulgate. It even became the textual basis for Luther’s translation into German, as well as Wycliffe’s translation into English. However, as many have noted, there are some significant limitations to Erasmus’s Greek New Testament. Strauss mentions four of these:

(1) Erasmus had a very limited number of Greek manuscripts available to him, only about a half dozen. All of these were later manuscripts from the Byzantine family. The oldest was from the eleventh century AD…(2) In various places, Erasmus gave in to pressure to conform to the Latin Vulgate—even when it conflicted with the Greek text [e.g., 1 Jn 5:7–8]…(3) In other places, Erasmus introduced words from the Latin Vulgate that are found in only a few late Greek manuscripts…(4) Erasmus only had one manuscript of the book of Revelation (copied in the twelfth century), but it was missing the last leaf with the last six verses. Erasmus therefore translated from Latin back into Greek.[3]

Since, Erasmus’s day, as we have already noted in our section on textual criticism, we have discovered thousands of Greek manuscripts which are much earlier than what Erasmus had access to, allowing us to have a much more accurate text from which to translate.

Language Developments and Reading Levels

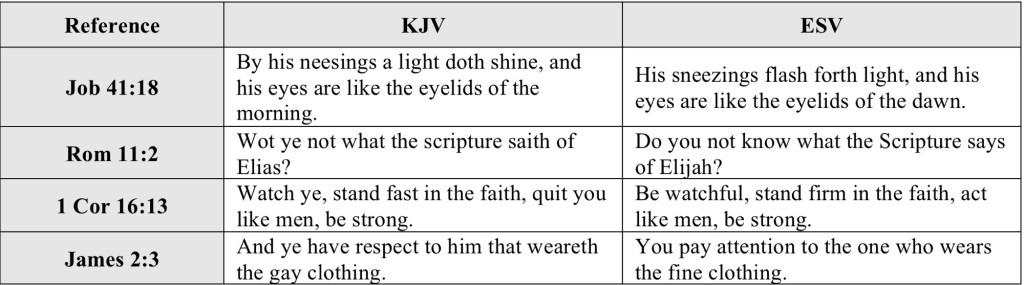

English is not a static language. Anyone who has tried to read Beowulf in the original Old English can attest to this reality. Over time, various influences slowly shift the meaning and usage of language. Consider the following examples:

Although this dynamic is most noticeable in differences between the KJV and modern translations, a similar dynamic is present between the modern translations themselves. This has less to do with language development but rather the translators’ target reading level. In general, the ESV requires a higher reading level than the NIV, which requires a higher reading level than the NLT, and so forth.

Exegetical Reasons

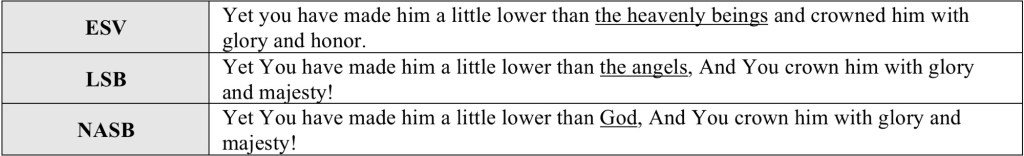

All translation requires some level of interpretation. Sometimes differences between translations arise from differing exegetical or interpretive decisions made by the translators. An example may be found in the different translations of Ps 8:5.

The point of contention in this example is the proper way to translate the Hebrew word elohim. The majority of the time, in context, it refers to God and is translated as such. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes, it refers to other false “gods,” or demons (see Dt 32:16–17). At other times, it refers to the angelic host that makes up his divine council (see Ps 82:1, 6).[4] Finally, it is also used to describe the spirit of Samuel whom the witch of Endor conjured (1 Sam 28:13). Since elohim can apply to each of these cases, the term deals more with the spiritual nature of an entity rather than his identity.[5] That means that the translation of the term becomes a matter of interpretation. In the example listed above, you are seeing the translators make different interpretive decisions on this matter.

What Translation Should I Use?

Finally, we want to address the question, “What translation should I use?”. While thought-for-thought translations certainly can be used with great benefit in personal devotion and public reading, for those who want to get inside the mind of the authors of Scripture and follow their flow of thought as much as possible and with the most precision, translations which lean more word-for-word will provide the most benefit. Beyond this, we want to use a translation that is made from the best available manuscript evidence. So, while the KJV and NKJV are excellent translations of their base text, they are not based on the most accurate manuscripts, thus limiting their usefulness to some degree. This is not to diminish their literary excellence or their usefulness in personal devotion, however if the KJV is your mainstay, it will benefit you to also have a more modern translation ready at hand. With these considerations in mind, translations such as the ESV, LSB, NASB, and to a lesser degree the CSB or NIV are best suited for the type of studying that seeks to understand the original meaning of the text. Further, in any study, it is helpful to have multiple translations on hand since their differences can alert you to interpretive difficulties that require you to slow down and think through.

[1] These categories are adapted from Richard Alan Jr. Fuhr and Andreas J. Köstenberger, Inductive Bible Study: Observation, Interpretation, and Application through the Lenses of History, Literature, and Theology (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic, 2016), 46–73.

[2] Strauss explains, “The name ‘Textus Receptus’ that is given to this Greek text came from an edition produced by the Elzevir brothers in 1633. The preface to this edition said that this Greek text was the ‘text which is now received by all’—in Latin, textus receptus” (Mark L. Strauss, 40 Questions about Bible Translation [Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2023], 233.).

[3] Ibid., 232–33.

[4] See Heiser’s discussion on this in Michael S. Heiser, Angels: What the Bible Really Says about God’s Heavenly Host (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 10–13.

[5] Ibid., 12.